Back then we called him The Banana Man. He was a creepy guy who never revealed his name. I had broken the cardinal rule that my mother repeated day after day while I was a kid growing up in 1970’s New York City.

“Don’t talk to strangers,” she’d say, “unless you want to get raped or kidnapped or killed.” Anytime there was a news story about a missing child my mother would nod knowingly. “See! The kid probably went with a stranger. Probably raped and dead by now! Those poor parents, what they must be going through!” Then would come her tirade. “You better not talk to strangers. You better not put me through that! If I find out you talked to a stranger, I’ll kill you myself!”

So, I am sure you can appreciate why I never told my mother about The Banana Man during the two-year period he stalked me.

By August of 1990 I was a grown woman who had long forgotten about The Banana Man. I working as a waitress at the Lion’s Head, standing at the service area, waiting for the bartender to deliver a couple of martinis, when the phone rang.

I picked it up. “Good evening, Lion’s Head,” I said.

“Hey, remember the Banana Man?” said the vaguely familiar voice on the other end.

“Who?” I said. “Who is this?”

“Ange? It’s you right? It’s me, Stephanie. Listen. I’m calling about The Banana Man. Remember him? You gotta look on page three of the Daily News. Go get the paper and read the article. It’ll freak you out. They say he’s the guy who kidnapped Etan Patz! Get the paper and call me back later!” Click.

I stood there for a moment, staring at the receiver in my hand, trying to figure out what my niece, Stephanie, was talking about and why on earth she would call me at work to tell me to read a story about Etan Patz, the boy who had disappeared on his way to the school bus in Soho back in 1979.

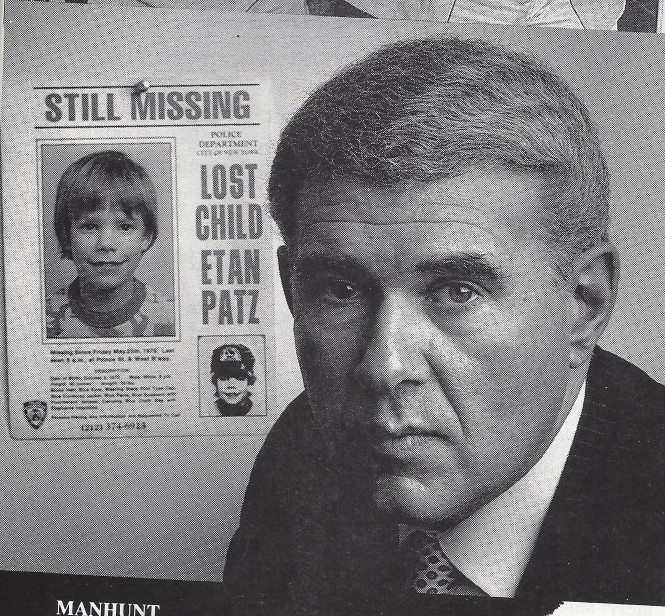

I found a copy of the Daily News tucked into the menu box at the waitress station. Located right next to the original Village Voice headquarters, The Lion’s Head was well known as a hang out for journalists and others of the writing persuasion. Thus, not unusual for a newspaper to be handy. I unfolded the paper, turned to page three, and stared at the photo.

And staring right back at me was the man who had stalked me back in the early 1970’s. The stranger I knew only as the Banana Man. In an instant, my head was flooded with a tsunami of Banana Man memories. But now, the Banana Man had a name – his name was Jose Ramos.

***

To the best of my recollection, the first time I met the Banana Man was in the spring of 1973, which would have made me eleven and Stephanie, my sister’s younger daughter, about seven years old. We were sitting on my stoop on West 12th Street with my classmate and friend, Vivian, having one of our “rummage sales”. We had just finished setting up our selection of old toys, knick-knacks and costume jewelry when a man was at our table eating a banana and inquiring about the price of a ring. It was strange, because he sort of just appeared and we were all taken aback when he spoke because none of us had seen him coming.

“This is a beautiful ring,” he said softly. “Beautiful like all of you.” We all smirked and looked away.

After an uncomfortable few seconds of silence he continued, “How’s business?”

“You’re our first customer today,” Vivian said. “That is if you buy something.”

“Hmmm,” he responded, fondling his long black beard. “What are your names?”

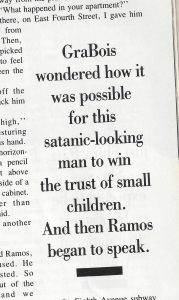

None of us answered. Instead of giving our names, Vivian started to point out items that he may have wanted to buy. As the man and Vivian talked about the items on display, I gave him a serious once over. His appearance was unique, but the fact was, we lived in Greenwich Village and “uniqueness” was really rather status quo. His long black wavy hair was thick and bushy, and it merged onto his face and neck in the form of sideburns, a beard and mustache – as though all one piece. He spoke softly from slightly up-turned lips which seemed frozen into a semi-smile, while his dark, down-turned eyes emitted a menacingly invasive stare. A velvet shirt, unbuttoned to the middle of his chest, hung on his lanky poor-postured frame. He wore a French beanie on his head, sandals on his feet and faded, frayed blue jeans making him look like a “hippie” to me. Slung over his shoulder was beat-up, dirty khaki-green knapsack which he held protectively close to his body. I found myself wondering what was in the bag.

“Bananas,” he said as though reading my mind. “They’re sweeter than candy and better for you too – would you girls like a bite of my banana?”

“No thanks,” we all replied in unison, eyeballing each other under raised eyebrows.

“Okay, Chiquitas,” he punned with uncomfortable familiarity. “It’s been nice. See you around.” He he turned and sauntered up the block away from us, meandering diagonally, jaywalking back and forth across the street like a slithering, urban snake.

“He was weird,” I said to Vivian.

“Yeah,’” she agreed. “Hope we never see him again.”

But I did see him again. In fact I started to see him all the time. If I were alone or with other kids he would go out of his way to approach and strike up a conversation; if I were with an adult, like my Dad, he would act as if he didn’t see me and would avoid eye contact – yet I could feel the invasion of his peripheral vision.

I had decided, and made my niece promise, that it would be better not to tell anyone about the man. Although I lived in constant fear of bumping into the Banana Man, I did not want to risk the humiliation of my father not believing me or, worse, the anger my mother would express at me for talking to a stranger.

No, I would dare not tell anyone. I would just try to avoid the Banana Man.

One day I was on my way to my dad’s apartment around the corner from where I lived with my mom. I turned the corner and walked right into the arms of the Banana Man.

“Hello my Chica,” he said. “All alone today? Where’s your friend, the flaca?” Unbeknownst to me at the time, “flaca” which means “skinny” in Spanish, was what he called my friend, Vivian, who he was also stalking. I couldn’t answer. I was paralyzed with fear. My heart raced wildly as my eyes darted around looking for someone, anyone. But there was no one. I never felt so alone and in danger. He took my right hand into his left hand, as though getting ready to Waltz and began to caress the inside of my palm.

“Come, Chiquita. Come with me,” he said from his mouth pressed into my neck. His hot and sour breath made me cringe. “I can show you things you’ve never seen before. Teach you how to feel good, my pretty little Chiquita. Come with me,” he whispered. “Come with me now.” I was immobilized against his body. In my mind I was writhing and trying to break free from his grip, but in reality my body would not move; I was reeling and thought for sure I would faint but was desperately trying not to; I was screaming wildly but no sound came out of my mouth.

And then – a miracle. The ground floor door to the apartment building behind me flew open smashing into my back while a man tried hopelessly to control the three frantic dogs at the end of their leashes. Startled, the Banana Man released his grip. I realized I was free and I ran, without looking back, until I reached my father’s apartment building, key in had. Only then did I look back to be sure he was not behind me ready to corner me in the vestibule.

I was safe in the building. I ran up the stairs, into my dad’s apartment, slammed the door and locked the deadbolt.

“Don’t slam the door,” my dad said from the living room.

“Sorry,” I squeaked back while I stood against the door, hyperventilating. I knew I had to tell my father what was happening but I felt like a dirty little girl and was scared my father would think I was too.

I gained my composure and walked into the living room. I tried to act “normal” but when I saw my dad I started to cry and then blurted out the whole story. Well, not the whole story. I was a terrified young girl, confused into believing that perhaps I was mistaken about the Banana Man’s intentions. Or, worse, maybe I had done something to lead him on.

As I told the story to my dad, I found myself minimizing the severity of the events. The final outcome of what I revealed was something to the effect of “There’s this weird guy who I see around my block a lot and I think he might be following me, but I’m not sure, it’s probably nothing, but I just thought I’d mention it.”

But as I stood at the window, telling my story to my dad, I could see the Banana Man! There he was, across the street from my dad’s apartment window, just standing there, eating a banana. He did not turn his face directly to me, he did not look up, but I knew he could see me. I motioned for my father to approach and as soon as my father was visible in the window, the Banana Man opened the lid of a nearby trashcan, discarded his banana peel and casually wandered up the block.

My dad wanted to go down and say something to The Banana Man. But I wouldn’t let him. I was afraid he would hurt my dad. I was afraid he would say something to make my dad angry with me. I begged my father to not confront the Banana Man.

***

It was the summer of 1975. I was thirteen, working as a junior counselor at a day camp on Sullivan Street. One morning I was greeting the children as they arrived when I saw the Banana Man. He was right up against the fence, two hands latched on to the chain linked rungs, eyes peering in. I was convinced he was there looking for me. I felt the blood rush from my face and the counselors who were closest to me immediately noticed that something was wrong.

“Are you sick? Do you want to sit down? Are you okay?”

I burst into uncontrollable sobs. “It’s him,” I said. “The Banana Man. He’s following me. I am afraid he’s going to kill me. Help me. Help me, please.”

Someone went to get the camp director, an older man we all called Mr. Z.

“Who wants to kill you?” asked Mr. Z.

“Him,” I said pointing to the man at the fence. “He’s been following me for two years. He grabbed me once. Tried to get me to go with him. I can’t take this anymore. Please make him leave me alone.”

When Mr. Z looked over at the fence, the Banana Man let go and started to head up the block towards Washington Square Park. Mr. Z. and several of the older boy counselors left the camp and followed the Banana Man. I went to the fence and saw the counselors chasing the Banana Man into an apartment building vestibule and Mr. Z. following.

Before I left the camp that day I was called to Mr. Z.’s office.

“Who was that guy?” he asked.

I told him the whole story and when I was finished he said, “You don’t have to worry about that piece of shit anymore. I told him that if I ever see him around you or this place again, I’ll break his fucking legs. He won’t bother you anymore. So don’t worry. Okay? And don’t talk to anymore strangers!”

After that day, I never saw the Banana Man again.

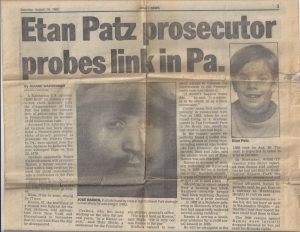

That is until his face was staring back at me from page three of the Daily News in August of 1990. I struggled to read the article through the dim light of the waitress station…

“A Manhattan U.S. attorney ‘hell bent’ on linking a convicted child molester with the disappearance of Etan Patz…because he believes Jose Ramos kidnapped Etan on May 25th, 1979…Ramos, 47, the boyfriend of a woman who babysat for the Patz children… Ramos told authorities he had met Etan in Washington Square Park the morning he disappeared and took him to his apartment…after the child refused his sexual advances…”

“A Manhattan U.S. attorney ‘hell bent’ on linking a convicted child molester with the disappearance of Etan Patz…because he believes Jose Ramos kidnapped Etan on May 25th, 1979…Ramos, 47, the boyfriend of a woman who babysat for the Patz children… Ramos told authorities he had met Etan in Washington Square Park the morning he disappeared and took him to his apartment…after the child refused his sexual advances…”

I finished reading the article which brought back my childhood terror of being on that corner in 1974, a scared little girl, trapped in the arms of The Banana Man/Jose Ramos.

I felt numb, then skeeved, then overcome with emotion.

I felt like I wanted to meet Jose Ramos at that moment, as an adult, to confront and pummel him for what he had done to me as a child.

I felt grateful when I remembered that Mr. Z had threatened to break his legs which ultimately stopped Jose Ramos from stalking me.

I felt love for my mother who, I suddenly realized, had probably saved my life with her brutally candid descriptions of all of the horrible things that could happen to an unaware kid on the streets of New York City. Although her methods were harsh, she had instilled in me the where-with-all to break free from Jose Ramos, to not go with him that day on the corner.

And then I shuddered at the thought that Jose Ramos, the man who had stalked me as a child was thought to be the same person who was responsible for the disappearance of Etan Patz.

Since reading the Daily News article in 1990, I have followed the Etan Patz case. I was relieved to learn that Jose Ramos was convicted and incarcerated in a Pennsylvania correctional facility for what would most likely be the rest of his life.

I have remained hopeful that some evidence would eventually emerge to determine once and for all if he is the person responsible for Etan Patz’ disappearance.

I listened to the news intently in 2012 when Pedro Hernandez “confessed” to the crime but I did not believe it. I have been following Pedro Hernandez’ trial which is taking place right now trying to remain objective. I feel so much compassion for the Patz family although I realize I cannot imagine their pain. Thus, in my heart I can only hope and pray that the outcome of this trial will be whatever Etan’s family needs.

But, my gut is telling me they have the wrong man on trial.

A recent story by the Huffington Post highlighted the alleged connection between Jose Ramos and the disappearance of Etan Patz: <Read the Story>